Hard as it may be to imagine, there was a time when Cleveland, Ohio was one of the largest cities in the entire United States. According to the 1920 census, Cleveland was ranked number 5 in population, right behind New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Detroit. By 1970 it had slipped in rankings to number 10, but by that point in time it still had 750,000 people living in the city proper. Today, in 2018, the city is home to only 388,000, though the metropolitan area still boasts a fairly sizable 2 million.

It comes as no surprise, then, that during the mid-20th century, when the area was a lot more crowded, that there were plans for numerous expressways to cross the area. Contrast with what Cleveland’s freeway system looks like today:

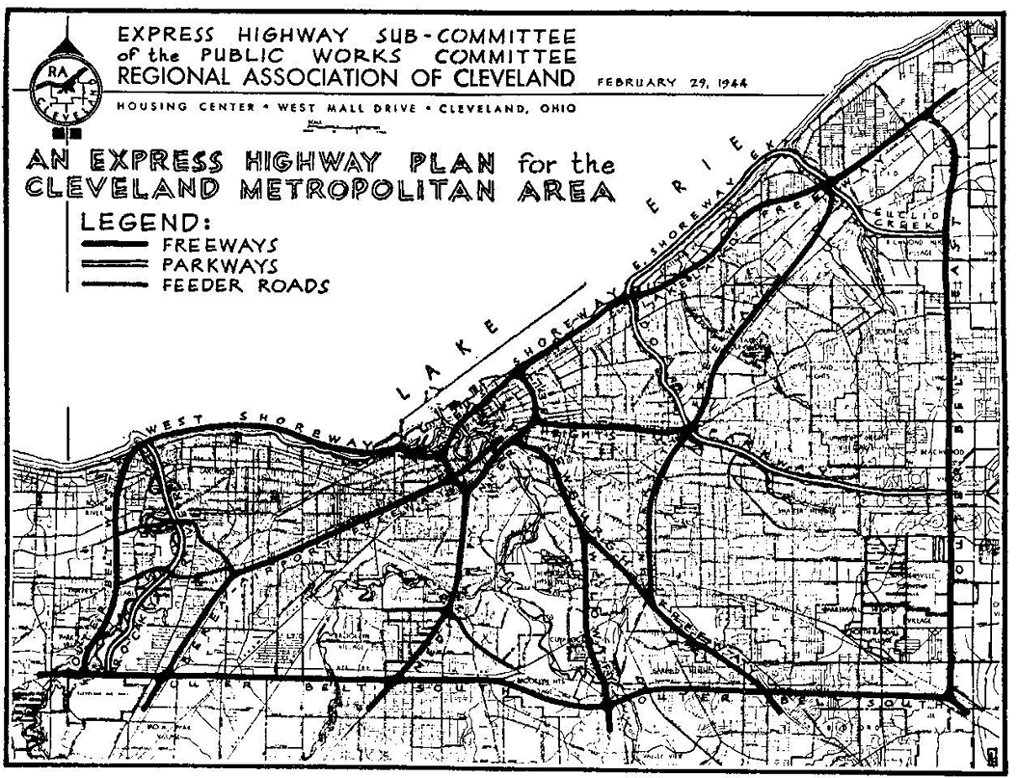

with the original plans from 1944:

During the 1950s and 1960s, the freeway plan for Cleveland underwent numerous revisions. One plan from the mid 1960s was considerably more ambitious in scope:

The “freeway revolts” that had begun out west during the late 1950s and early 1960s — including the fight against San Francisco’s Embarcadero freeway — eventually spread to the eastern cities a few years later. As a result, Cleveland’s freeway system sat with multiple gaps and pieces marking uncompleted highways. Until the mid-1980s, traffic traveling on I-480 had to make use of Brookpark Road between much of the area between I-71 and I-77. The Jennings Freeway (Ohio State Route 176 between I-71 and I-480) sat in limbo for many years before being finished in 1998. The only segment of the Parma Freeway to see completion was the northbound exit off I-71 to Denison Avenue.

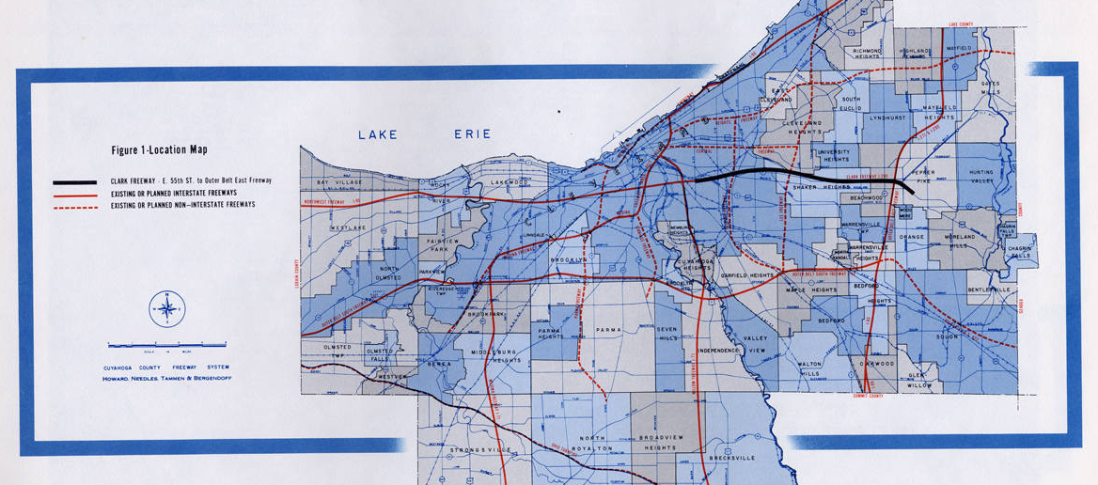

The saga over the Clark Freeway played out throughout the 1960s. The original plan for the Clark was to connect I-90 and I-71 near downtown with I-271 (“The Outerbelt”) in the eastern suburbs. The proposed freeway, which was originally to be designated as I-290, was to run in a straight east-west line through the eastern part of the city and the suburbs of Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights, as the above map shows with the black line. Many residents of the two suburbs were particularly aghast at the prospect of having their communities carved up not only by the Clark but also the proposed Heights and Lee Freeways, which were later canceled. Of particular concern was the probability that the elevated 8-lane Clark would have a negative environmental impact on the Shaker Lakes Nature Preserve, which included Horseshoe Lake:

The fight against the Clark reached a peak in 1969. Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes, known for his pro-highway stance and lack of interest in environmental issues, had been pushing for construction of the Clark, fearing the loss of federal funding for the state. Residents of Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights, who had already formed committees to block the highway, found an ally in Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes. If there was one concern that the city shared with the eastern inner suburbs, it was the potential loss of residents and economic activity to Cleveland’s more distant suburbs. Rhodes, who was planning to run for the U.S. Senate, realized that he needed the support of Cleveland’s inner suburbs if we was to achieve victory. An additional factor that played a major role in stopping the Clark was local newspaper editor Harry Volk, who kept the issue alive every week in the area papers, discussing the negative impacts future freeway construction would cause. By 1970, the plan to construct the Clark through Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights was pretty much dead.

That, however, was not the final end of the story. Years later, a portion of the Clark Freeway WAS completed and opened to traffic in 1990, with the designation of Interstate 490. The 2 1/2 mile highway runs from its western terminus at its intersection with I-90, I-71, and the Jennings Freeway to its eastern terminus at East 55th Street.

Near the western terminus of I-490/Clark Freeway, facing west.

At the eastern terminus of I-490 and East 55th Street. As of 2018 there are no plans to extend the freeway further east.

At the eastern terminus of I-490 and East 55th Street. As of 2018 there are no plans to extend the freeway further east.

Additional sources:

http://www.gcbl.org/blog/2015/02/clevelands-1969-highway-revolt-sheds-light-on-opportunity-corridor

http://www.clevelandmemory.org/freeways/index.html

Great images and story. Never been to Cleveland, but it appears an interesting city.

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words, Larry! My dad and his family are originally from Cleveland, so I’m actually very familiar with the area. The city went through some pretty rough times during the 1970s and 1980s, but it seems to be gradually re-vitalizing itself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a Rand McNally from 1980 that has I-480 ending at Brook Park and not getting completed until the weird spur at exit 12 (eastbound only). The segment from Tiedeman east to Brook Park wasn’t completed until 1988 I think.

Same with Minneapolis’s I-494–there is a segment where it became a 4-lane road near Mendota Heights–they hadn’t built the remainder of the road yet until the late ’80s!

LikeLike

They stopped a freeway for a “a two-bit duck pond.” lol

Albert S. Porter was a jerk.

LikeLike